Tourist/Purist

Virgil Abloh is moving. A recent scan of his Instagram feed shows images from Paris, Chicago, New York, Vancouver, and Spain. The multidisciplinary designer, creative director, DJ, and artist travels 310 days a year; each trip meticulously documented on Instagram for his 4.2 million followers. As the menswear artistic director of Louis Vuitton; propeiter of his own label, OFF-White; collaborating with everyone from Ikea to Evian, Tamara Murakami to Nike; DJing at Coachella; and for ten years, as Kanye West’s creative director, designing the covers for Yeezus and Watch the Throne, art directing tours, and designing merch, Abloh seems to never be still. His iPhone is his studio, WhatsApp his conference room.

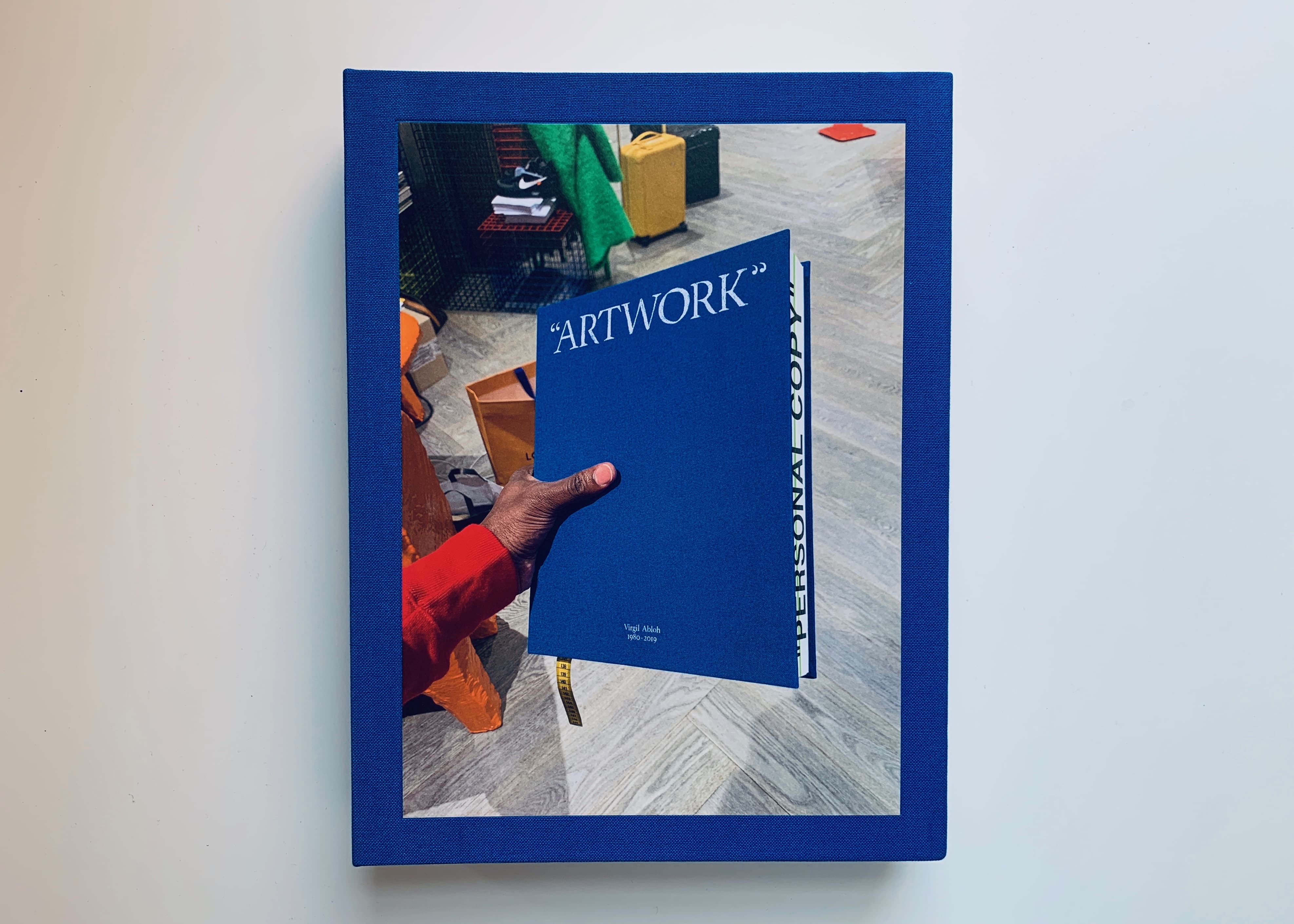

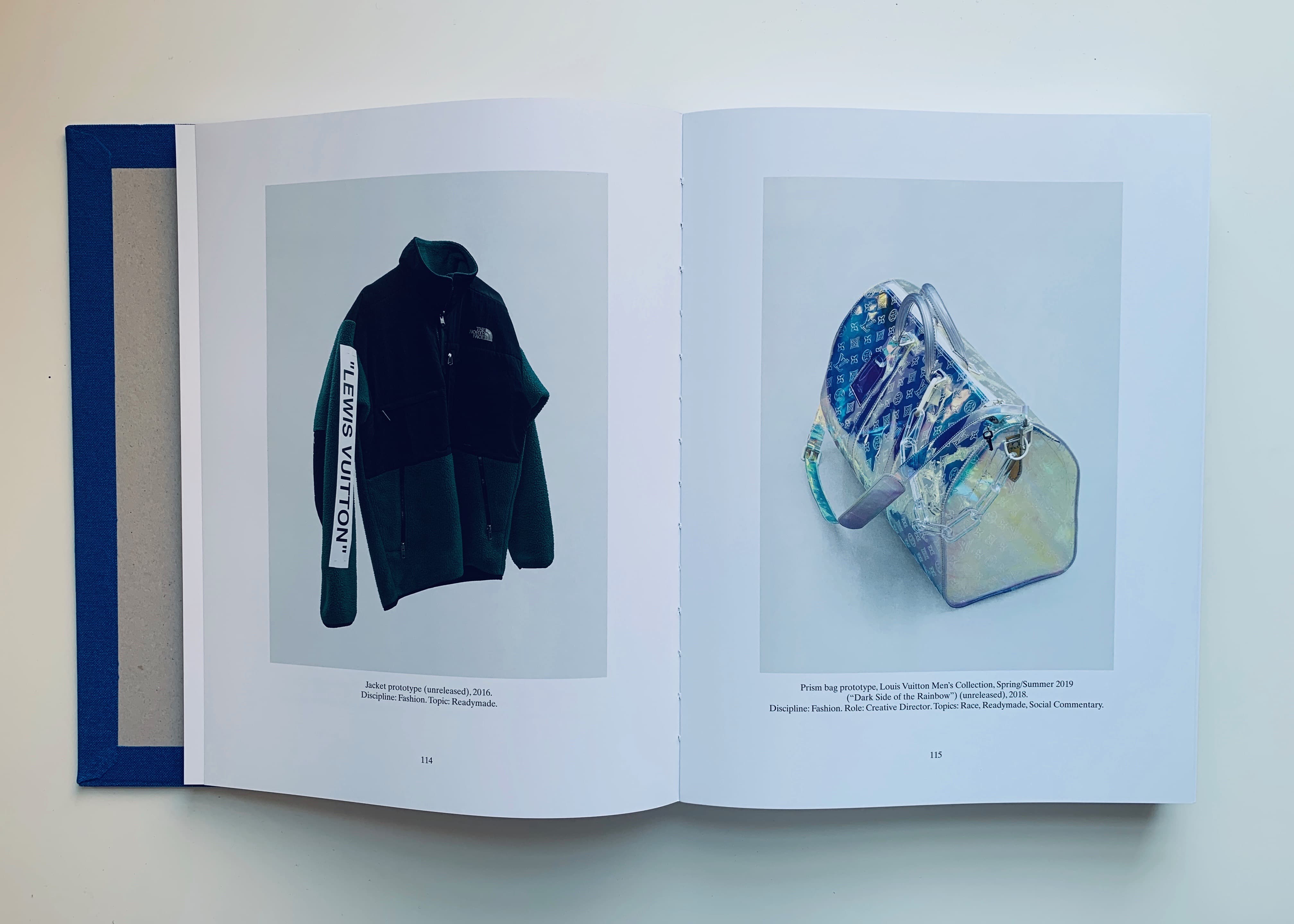

A mid-career retrospective of this work, curated by Michael Darling titled “Figures of Speech”, is currently on display at Chicago’s Museum of Contempoary Art. The accompanying publication is as unusual as its subject — more than a simple exhibition catalog, it was designed and edited in close collaboration with Abloh, includes texts from poeople like Michael Rock and Taiye Selasi, a conversation with Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal of AMO (who also designed the MCA exhibition), and a visual index of everything Virgil’s worked on dating back to his thesis as an architecture student at the Institute of Technology in Chicago. Seeing his work organized around medium (graphic design, fashion, photography, fine art, product, etc) and theme (race, social commentary, readymade) a new reading of his work begins to emerge. His highly visual, pop culture referencing work can, at times, obscure the thinking behind it all. Indeed, his trademark typographic gesture — all-caps Helvetica in quotes (never smart quotes!) — suggests an ironic distance that hides the depth of his process. But in the pages of Figures of Speech,, Abloh’s deep knowledge of design and art history are front and center. Looking at this work in one-sitting, however, I was struck by the consistent train of thought that runs through an at-first-glance skitzophrenic body of work. The portrait of an artist reveals itself.

Abloh, the son of Ghanianan immigrants, grew up in Chicago, obsessed with punk music, skateboarding, and art. Originally studying engineering as an undergraduate to please his immigrant parents with a suitable degree, he tried to find a way to express himself artistically. Architecture was a logical way to build upon what he learned in engineering school. While in school, he started designing his own t-shirts and upon finding out the printshop where he worked part-time and printed his own designs, was also the shop that printed Kanye West’s merch, he purposely left a few of his designs out in the opened when he knew West’s manager would be there. As hoped, his designs’ caught his eye and made their way back to the then-rising Chicago rapper. Abloh started design shirts for West, gaining more autonomy, ultimately becoming West’s Creative Director designing everything from stage sets to album covers. When West got interested in fashion, it was Abloh who interned at Fenti with him, learning the ins and outs of the industry, preparing him for the career he was beginning.

Abloh’s architecture background should not be overlooked; this origin story comes up again and again in the texts in the book and clearly influences everything he has done since. The conversation with Koolhaas and Bantal is, in the end, a conversation about the expanding nature of architecture and how Abloh, through thinking like an architect, applies this education to everything from garments to album covers to runway shows. Much like Koolhaas, in fact, Abloh sees architecture as an expansive discipline, not reserved for simply building buildings. (His 2015 talk at Columbia was called “How Architects Can Change the World by not building Buildings.”) If architecture, then, is a way of thinking, a way of seeing the world, Abloh’s taking this approach and applying it to everything he can.

This is, perhaps, the model of the new designer. The silos in the design industry are falling a way — fashion designers need to understand graphic design, graphic designers should look to architecture, architects are looking at product design. The cross-pollination of industries and mediums creates new types of designers and new types of work. The old-fashioned ideas of the multi-hyphenate designer or the ‘designer as X’ suddenly seem antiquated. For Virgil Abloh, it’s all one in the same. It’s all design. He moves between mediums; blends high and low; a relentless self-promoter, skilled at social media; well-versed in both art and design history and contemporary culture.

“Off-White”, explains Virgil Abloh of the name of his fashion brand, “is about the grey area between white and black.” Abloh’s entire oeuvre, of course, lives in this grey area: not just in medium or discipline but also high and low, insider and outsider, historically aware and culturally attuned, accessible and exclusive. He calls himself a tourist and a purist — simultaneously touring other fields while bringing his own background with him, both student and teacher, novice and expert. “When you touch on so many different creative activities, none of them can really be seen as central. To be OFF- then is a kind of working philosophy,” said Michael Rock when he introduced Abloh for a lecture at Columbia, “It means OFF-track, OFF-tune, OFF-message, OFF-balance, OFF-kilter. At the heart of it, to be OFF-White is to be OFF-center. And Virgil proves over and over, we should forget the center, the edge is where the action is.”

What Abloh seems to get better than many of us is that we’re are all postmodern now. We all blend references, we borrow and remix. The next generation of designers, already savvy brand builders on social media, aren’t interested in disciplines, or historical movements. To them, it’s all the same, free for the taking. Abloh’s described his design philosophy as changing something by at least three percent. “Duchamp is my lawyer” he’s famous for quipping. But this too, of course, isn’t new at all but rather a reclamation of an older type of design practice. Until this generation, designers were always polymaths. Think Munari, the Eames, Malholy-Nagy, Albers. These designers’ careers are equally hard to classify, moving between architecture and graphic design and children’s books and photography and painting and teaching. Abloh, isn’t merely remixing, borrowing, adapting, he’s also reclaiming an older definition of design, updating it for a new generation.

Off-White, then, is a metaphor, a symbol of the thread that connects an otherwise disjointed career. To be on the edges is to constantly be shifting between groups and tribes, styles and movements, disciplines and mediums. The only way to find the edges is to keep pushing, to exploring, keep moving. “What is the marker of good design?” asked Frank Chimero in the beginning of his 2011 book, The Shape of Design, “It moves.”