Experimental Jetset’s Statement and Counter-Statement

What goes into a design monograph? As I scan the massive books on my shelf, it’s tempting to see the genre as a fixed form of another era. Upon closer inspection, however, I can find a lot of variety in their structure, their content, and how they choose to represent the designer. On one end, there’s the chronological record of one’s work with commentary from the designer. I’m thinking about the classic structure of Michael Beirut’s How To or Peter Mendelsund’s Cover, which aim to be a complete portfolio of the work. There are also the historical, indispensable monographs edited and written by someone else to honor a designer of the past, like Steven Heller’s books on Alvin Lustig and Paul Rand. And far on the other end you can find things more experimental, more extreme, harder to describe. Two of my favorite monographs sit at this end of the spectrum—Rem Koolhaas and OMA’s SMLXL and Alan Fletcher’s The Art of Looking Sideways

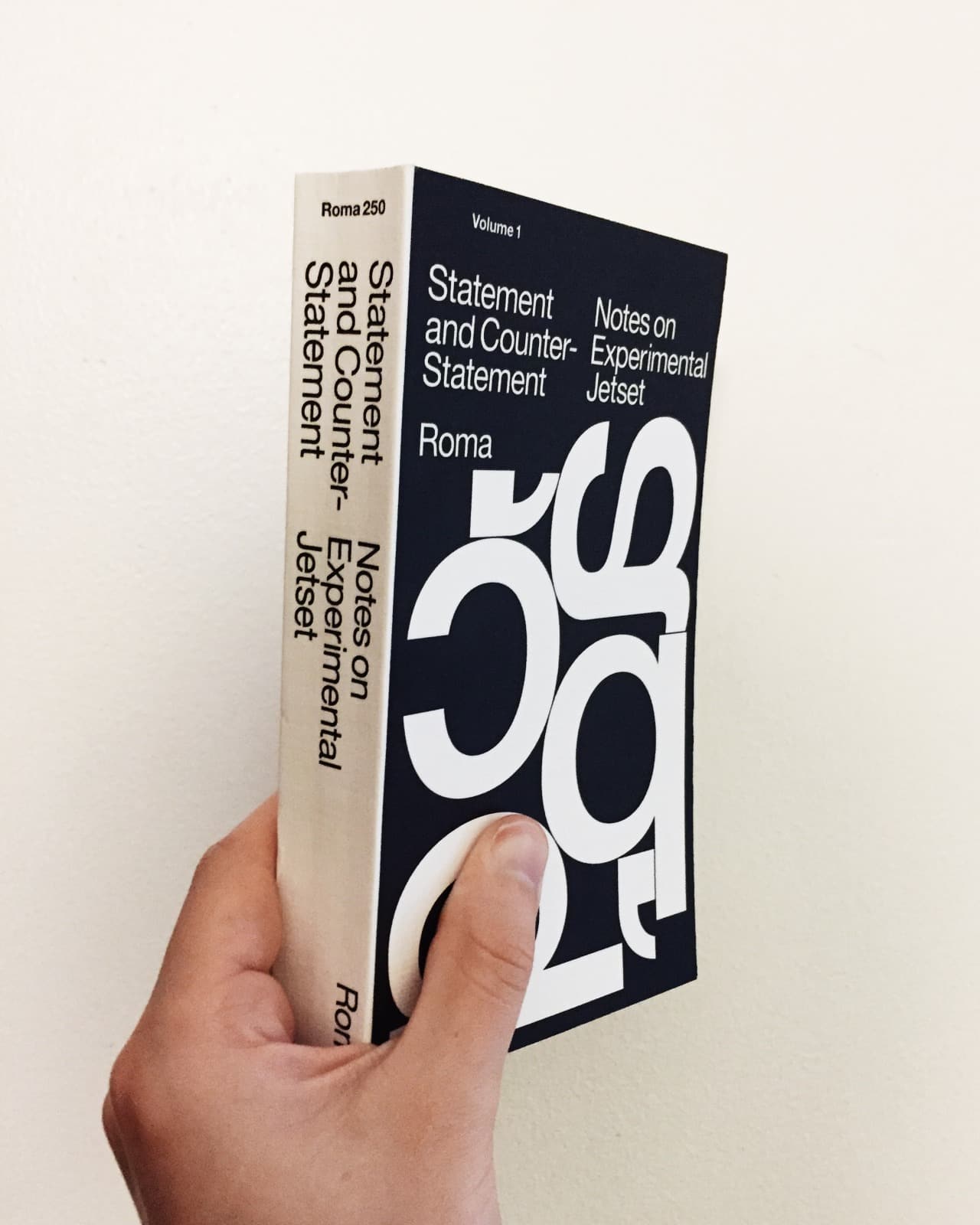

Experimental Jetset’s Statement and Counter-Statement clearly falls into the latter category. For the first published book of the Amsterdam-based design trio’s work, the studio opted for a nearly six-hundred page pocket-size format that doesn’t show any full images of their work. Instead, the book is filled with cropped black and white images of the studio’s two decades of work, reproduced at 1:1 scale, and a series of essays written by friends and influences. In fact, aside from the images, the studio barely makes an appearance in the book at all.

Even the essays they’ve included never mention Experimental Jetset explicitly but rather touch on themes found in their work and ethos. Linda Van Deursen’s—one-half of the studio Mevis & Van Deursen—pens three essays that look at different photographs to ruminate on modernism. The Power of Three, a wonderful essay from designer and writer Mark Owen, charts the history of the rock band model culminates by placing Experimental Jetset into this history without ever mentioning their name. The restraint and literary flourish make Owen’s piece a quiet highlight of the book.

The most interesting chapter in the book, however, is Jon Sueda’s ambitious “Index of Fragments”—an alphabetized index of quotes from various Experimental Jetset interviews. Removed from context, the answers are grouped under simple headings that reveal the studio’s preoccupations: words like Helvetica, criticism, Marxism, punk music, language, authorship, etc. I think of this chapter as the text version of image chapters—by removing the context and placing similar themes together, you start to see more intimately how the studio thinks about their work, how it’s evolved, and how they’ve grown. The title—Statement and Counter-Statement—manifests itself here when you read quotes back to back that seemingly contradict each other.

“Truth becomes something living;” writes Walter Benjamin in the quotation from which the book finds its title, “it lives solely in the rhythm by which statement and counterstatement displace each other in order to think each other.” Benjamin is another figure who’s clearly influenced the studio’s entire output and the structure of the book. The book opens with another Benjamin quote and one can’t help but draw parallels to The Arcades Project—Benjamin’s literary collage about Paris that’s considered the forerunner to post-modernism—as an inspiration for the book’s format.

Spending time with this book over the last few days, I tried to remember where I first saw Experimental Jetset’s work or when I learned about their studio and I couldn’t figure it out. I’ve been following them for nearly as long as I’ve been a designer. It’s fun to see projects I’ve admired over the years sit next to each other in Statement and Counter-Statement, from the EP book covers to the Whitney identity, the SMCS bulletins to the Helvetica film posters.

These convergences reveal Experimental Jetset’s curious place in the larger design canon. It occurs to me that they are one of the few studios we can confidently call auteurs. Flipping through these pages, as projects and quotations blur together, spanning twenty years, a decidedly clear worldview, a consistent practice, emerges. They’ve been able to operate at the fringes of the field, consistently enacting their theories and aesthetics in projects large and small, from small European publishers to large American museums, with equal rigor and authority. This is a book about the rock band that retains their independence even when playing on the main stage.