The Power Broker

The book has been sitting on the table next to my bed for two years. I spotted a few of them in the corner of a used bookstore in San Francisco’s Mission District and I had read an essay about Robert Moses earlier that week. It was an impulse purchase. I had to buy it.

It moved with me across the country, finding its spot on the new table next to my bed in my new apartment. I’d occasionally pick it up and read a few pages or look at the inset photo pages. But it was big and it was heavy and I knew it was one of those books that waits for you to be ready for it. You need to be ready for it.

About a month ago, I realized I was ready and I finally picked up Robert Caro’s epic biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker, and read the first page. And then the second and the third. Before I knew it, I was deep into the 1,100 page story and I couldn’t stop. I was halfway through it when I realized this was one of the best books I’d ever read. [[MORE]]

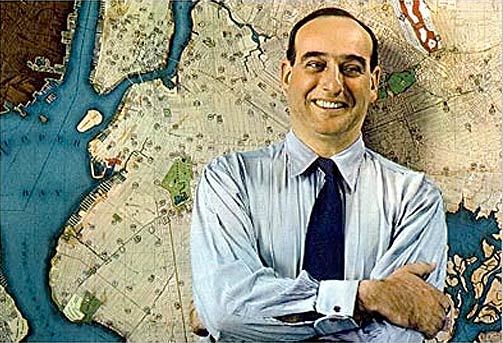

Robert Moses was a city planner, working primarily in New York City and Long Island, who built some of the first New York state parks, many of the city’s bridges and highways. More than any other individual—more than any mayor or governor or president— he shaped New York City. In the introduction to The Power Broker, Robert Caro writes:

He built the Major Deegan Expressway, the Van Wyck Expressway, the Sheridan Expressway and the Bruckner Expressway. He built the Gowanus Expressway, the Prospect Expressway, the Whitestone Expressway, the Clearview Expressway and the Throgs Neck Expressway. He built the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the Nassau Expressway, the Staten Island Expressway and the Long Island Expressway. He built the Harlem River Drive and the West Side Highway.

Only one borough in New York City—the Bronx—id on the mainland of the United States, and bridges link the island boroughs that form metropolis. Since 1931, seven such bridges were built, immense structures, some of them anchored by towers as tall as seventy-story buildings, supposed by cables made up of enough wire to drop a noose around the earth. Those bridges are the Triborough, the Verrazano, the Throgs Neck, the Marine, the Henry Hudson, the Cross Bay and the Bronx-Whitestone. Robert Moses built every one of those bridges.

You quickly realize, however, that this is not simply a story of city planning or a simple biography of one man or how New York became the city it is. “Power is not an instrument that its possessor can use with impunity,” Caro writes on page nineteen, “It is a drug that creates in the user a need for larger and larger doses.” He spends the next thousand pages telling a story about power and Robert Moses’s addiction to it. This is a book about how an idealist with grand plans for parks and roads realizes the only way to turn these plans into reality is not simply through money or politics or idealism, but through power. And after Moses experiences what power can achieve, that power is no longer a means to his larger goals, it becomes the goal.

In a New York Times profile on Robert Caro from 2012, Charles McGrath writes: “These stories still fill him with outrage but also with something like wonder”. That’s exactly the feeling I had reading The Power Broker. I could hold two, sometimes opposite, opinions in my head at the same time: outrage at his blatant racism, his arrogance, his sometimes-revenge driven policies, the ease for which he could dispose of people no longer needed to help his cause. Yet at the same time, you can’t help but feel awe: there are few people who accomplished as much as he did, the amount, the scope, and the size of what he built is grand on every scale.

That is the sign of a great biography, I think: the ability to hold opposing views of the subject at once. It should not be entirely dismissive or entirely adulating, for one without the other cannot paint the full portrait of an endlessly complicated individual and his legacy. I would think often about Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs while reading The Power Broker. I had just seen the movie adaptation and left wanting more. What Caro could have done with Jobs would have been amazing, I thought. It’s easy to want Robert Caro to write every biography after finishing The Power Broker. You start to see his themes everywhere, drawing parallels between Moses’s story and today’s political and cultural landscape.

And as if it were a Shakespearian drama, Moses’s quest for power also leads to his fall. The processes, the methods, the tricks he used to amass his vast power over city and state governments— while never being elected to a public office—were the same processes, methods, and tricks that backfired on him. Once a man who held a dozen leadership positions in New York for four decades, he died having lost it all; his power stripped of him, his legacy controversial. Despite everything he’d done in the quest for power, despite the complicated nature of his legacy, his fall felt tragic. I finished the book with mixed feelings.

Last year was the fortieth anniversary of the release of The Power Broker. Caro reflected on the book’s last sentence—a question, “why weren’t they grateful?”—for The New York Times:

Why weren’t they grateful? As I recalled that Exedra scene in 1969, as I was trying to organize my book, I suddenly knew, all in a moment, that that question would be its last line. For the book would have to answer that very question, would have to answer the riddle posed by the Moses Men: How could there not be gratitude, immense gratitude, to the man who had dreamed a great dream — of Jones Beach and a dozen other great parks, and of parkways to reach them — and who to create them had fought, and won, an epic battle against Long Island’s seemingly invincible robber barons? How could there not be gratitude to the man who had built mighty Triborough, far-stretching Verrazano, who had made possible Lincoln Center and the United Nations? And yet there were ample answers to that question. Did I think in that moment of Robert Moses’ racism — unashamed, unapologetic? Convinced that African-Americans were inherently “dirty,” and that they don’t like cold water (“They simply didn’t like swimming unless it was red hot,” he explained to me confidentially one day), he kept the water temperature deliberately frigid in pools, like the ones at Jones Beach and Thomas Jefferson Park in Manhattan, that he didn’t want them to use. Did I think of the bridges he built that embodied racism in concrete? When he opened his Long Island parks during the 1930s, the only way for many poor people, particularly poor people of color, to reach them was by bus, so he built bridges over his parkways too low for buses to pass. Or of the “slum clearance” projects he built that seemingly created new slums as fast he was clearing the old, or of the public housing he placed in locations that cemented the division of New York by race and class? Did I think in that moment of the more than half a million people he dispossessed for his projects and expressways, using methods that led one observer to say that “he hounded them out like cattle”? Did I think of how he systematically starved New York’s subways and commuter lines for decades and blocked proposals to build new ones, exacerbating the region’s dependence on the automobile? I don’t remember exactly what I thought of when I remembered Robert Moses’ speech at the Exedra — only that in that moment, seeing the book’s last line, I suddenly saw the book whole, saw the shape of everything that would lead up to that line. I began organizing the book, the thoughts coming faster, I recall, than I could write. Over the next days, I outlined the book — in a quite detailed outline — from beginning to end. Some parts of what I wrote from the outline would later have to be truncated or cut out entirely so that the book could fit into one volume; aside from these deletions, “The Power Broker” as it was published follows that outline all the way through.

Why weren’t they grateful? Robert Caro ends The Power Broker with a question, but he’s already answered it. This book had been sitting next to my bed for two years and since opening it a few weeks ago, I haven’t stopped talking about it to anyone who will listen. Sometimes I’m praising him, admiring the vision, in awe of his accomplishments. Other times I’m disgusted, asking how someone can get away with what he did, hold so much power without ever being elected to office. And perhaps, sometimes, I’m trying to justify him, explain him, trying to figure out my own feelings.

In some stories there are good guys and bad guys. In some stories you can’t tell the difference between them. And in some stories, they are the same person. Robert Moses was one of those people, the line dividing the two sides blurry at times. Robert Caro’s biography paints a picture of an endlessly complicated and fascinating individual whose legacy will live on, constantly debated, for generations to come.

Robert Moses built parks and bridges and highways in hopes that that legacy would outlive him; he dreamed of parks and highways named after him. The Power Broker is one of the best books I’ve ever read, one I’ll be thinking about and wrestling with for a long time; one I’ll be recommending and forcing upon anyone who will listen for many years. Perhaps in the end, Moses got the only thing he ever really wanted: immortality.