Oak Ridge and the Architecture of the Manhattan Project

For the last few months, in little bits, I’ve been reading Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb (I like my summer reading light and breezy). I was immediately pulled into the narrative, with Rhodes’s literary style reminding me, at times, of Robert Caro’s. It’s an epic, all-encompassing history packed with science, intellectual ideas, and personal drama. Now, about 500 pages in, we arrive at Los Alamos and government focus on actually building an atomic bomb.

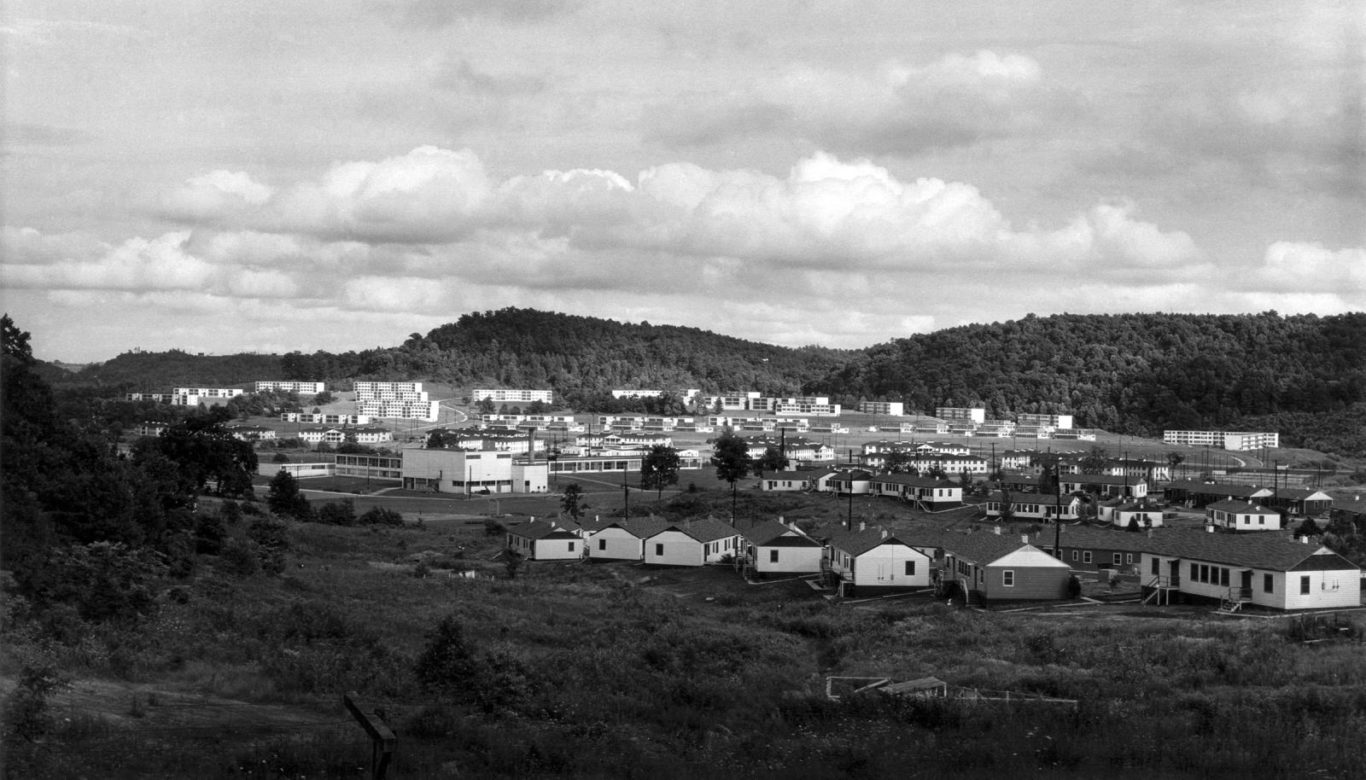

In this section, Rhodes writes about the other planned communities the government spun up quickly to house the scientists and workers near the sites. My interest was piqued reading about Oak Ridge, TN, a previously 60,000 acres of farmland purchased by the federal government in 1942 to house 75,000 residents at a production site for the Manhattan Project. Oak Ridge, especially is interesting, because it was constructed with assistance from Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, the massive architecture firm now known, simply, as SOM.

Here’s a Fast Company article about Oak Ridge from 2018:

In 1942, a secret city was born. Nestled in a valley in eastern Tennessee, the city–today known as Oak Ridge–would become the birthplace of the most dangerous weapon humanity ever created. But Oak Ridge isn’t just a glorified military base, built in the midst of World War II to prepare the U.S. to defend its interest. It was also a marvel of architecture, urban design, and planning, a community built to attract the greatest scientific minds of the generation to rural Tennessee to work for the government.

Robert Oppenheimer apparently wanted SOM to create a community that was alluring to woo academics from their jobs to come work for the government. SOM’s design consisted of a collection of single-family, pre-fabricated homes surrounded by a large green space and a network of roads, connecting the residential area to dormitories, schools, grocery stores, and barber shops. On SOM’s project page, they describe Oak Ridge as “an important step in the evolution of American urban planning and a catalyzing agent for the firm to think about the processes and principles of urban planning.” The design would then go on to influence and shape later planned communities including Reston, Virginia and Columbia, Maryland.

Also in 2018, the National Building Museum staged Secret Cities: The Architecture and Planning of the Manhattan Project that showcases the design and construction these “secret cities” the government built: Oak Ridge, Los Alamos, and Hanford, Washington:

The Manhattan Project would not have been possible without the extraordinary achievements in architecture, engineering, and planning that yielded three entirely new cities in a remarkably short time. Built in the early years of the modern movement, these cities reflected cutting-edge ideas about town planning, mass housing, civil and mechanical engineering, and modular construction. They became important proving grounds for the large-scale suburban development that would dramatically alter the physical and cultural landscape of the nation in the post-war era.

“Oak Ridge was heavily influenced by the planned community movement or garden city movement–an effort to make a connection between people and nature, to really try to undo the ills and problems of urban life in that day and age, and create places with green space–things that now don’t seem that strange, the curator Martin Moeller told Fast Company. “The fact that they set out to try to create single-family houses, separated by green space for all these people in an emergency situation is extraordinary.”

Here’s Heather Corcoran in The Architect’s Newspaper:

Not only would the town prove a testing ground in which Bauhaus and other early modernist principles were utilized to create the type of planned suburb development that would dominate the following decades, it was also an opportunity for SOM’s designers and engineers to experiment with new techniques and technologies, using prefab and modular construction methods combined with cemesto panels (names for their a mix of concrete and asbestos). At the time, the work was strictly confidential—not even the residents of the secret cities knew what they were working on. In The Guardian, David Smith, notes how despite the speed and secrecy, SOM was still very much operating of its time and the politics of community were also designed right into Oak Ridge:

SOM’s initial plan called for a “negro village” at the eastern end of town, furthest from the work sites, which was to include housing similar to that provided for white residents. But as Oak Ridge grew quicker than expected, those plans were abandoned and most African American residents were relegated to “hutments”: rudimentary plywood structures barely superior to tents.

In an optimistic twist, however, the first two public schools to desegreate in the south were in Oak Ridge.

I’ve had an interest in planned communities like this for a long time but somehow had never come across Oak Ridge before, but it immediately reminds me of my ongoing research on Disney’s architectural projects. What’s amazing about Oak Ridge is that it was built in a mere 6 months. And just two years later, the United States would drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

Oak Ridge still exists — as do the other two cities — and they are all still part of the military industrial complex. Oak Ridge, today, is a leader in renewable energy research. SOM, too, is still involved: in 2015, they worked on the Oak Ridge National Laborary, a 3D printed building, with the US Department of Energy.