March Readings

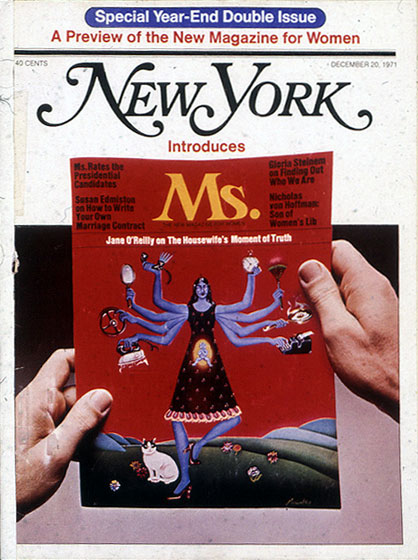

Milton Glaser, New York Mag / Ms. Double Issue (1971)

Milton Glaser, New York Mag / Ms. Double Issue (1971)

Two good stories from Art in America’s “Research Art” issue — the first on evaluating and defining the term:

On the institutional front, art schools have been establishing programs and centers for “artistic research” and “research-creation,” particularly in Canada and across Europe, for more than 20 years. In 1997 the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki established an early notable doctoral program for artists; two decades later, PhD degrees in art are available in multiple countries. Globally renowned curators such as Catherine David, Okwui Enwezor, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, and Ute Meta Bauer made their careers organizing large-scale international exhibitions often laden with research-based art and organized within a curatorial framework predicated on theory. Now, there are professional artists with research-based practices teaching their students various research methodologies and encouraging the production of yet more research-based works.

The current trend has an even longer historical trajectory when related to artists and their motivations. One might find traces in the work of Leonardo da Vinci or 17th-century naturalists such as Maria Sibylla Merian. Hito Steyerl, a contemporary research artist par excellence, describes the formal and semiotic investigations of Soviet avant-garde circles in the 1920s as formative for research art today. In her 2010 essay “Aesthetics of Resistance? Artistic Research as Discipline and Conflict,” Steyerl discusses authors, photographers, and self-proclaimed “factographers”—including Dziga Vertov, Sergei Tretyakov, Lyubov Popova, and Aleksandr Rodchenko—whose epistemological debates centered on terms such as “fact,” “reality,” and “objectivity.” From Constructivism, in which artists were redefined as designers, technicians, and engineers engaged in developing new approaches to constructing forms, emerged the program of Productivism and the associated method called “factography.”

And the second is a critical look at the opportunities and limits of Forensic Architecture:

Weisman’s often-quoted comment expressing suspicion about the award suggests that FA was indifferent to the art world until institutions came along, and only then begrudgingly acquiesced in the interest of greater visibility for their causes. But this is not how it happened. When I reached out to Anselm Franke of HKW, who cocurated FA’s inaugural exhibition with Weizman, Franke said that at the time he was a member of the group (or, in his words, “a double agent”). On its website, Forensic Architecture members designate themselves and HKW as the show’s co-funders.

Weizman said in a 2018 Frieze interview that “the decision to show things in exhibitions is made in consultation with the lawyers and families involved.” But this does not always resolve the uncomfortable dynamic at play when it seems as if FA is making a career exploiting peoples’ trauma. Often, they show the research years after the cases have been closed, and it isn’t always clear who benefits from the display.

These dynamics are most suspect in works that focus more on the group’s innovative uses of technology than on human rights violations. FA almost always presents its findings in the form of interactive online platforms, or as videos with didactic voiceovers that explain the situation and the investigative process. The group says that the goal of these explanations is transparency: they are making their methods open-source so that others can replicate them. But too often, in effect, FA’s impressive handling of the technology becomes the narrative’s protagonist.

The Button Pushing Impresario of Balenciaga

Jay Caspian Kang asks “what’s the point of reading writing by humans?”:

None of this output makes me feel concerned about being outmatched by the model, but it does make me wonder if I’ve been asking the wrong questions about it. We can disagree on whether A.I. can generate writing that could be convincingly passed off as mine—I think that, eventually, it will be able to do this—but I think you and I can agree that neither of us would want to read an article with GPT-4 (or 5 or 6) on the byline. Surely some L.L.M. down the line will be able to compose a more accurate assessment of DeSantis’s chances at winning the Presidency than its human counterparts in the political-pundit trenches, but what would be the point of that? I enjoy reading human writing because I like getting mad at people. Perhaps the personal quality in writing is a happy accident, and a lot of journalism could be replaced with an immense surveillance state with a GPT-4 plug-in. But the reason we read books and listen to songs and look at paintings is to see the self in another self, or even to just see what other people are capable of creating.

Instead of focussing on the viability of GPT-4’s compositions and whether they’re “better” or “worse” than my own, or fixating on the cringey clichés it generates—“long, winding road,” “careful tango”—I should be asking you, the reader, if you will still want me after the machines take over, and you should ask me if I still want you. The answers to both, I hope, are still yes.

On unpacking Michael Sorkin’s library:

Michael Sorkin moved his library many times, each relocation of his office prompting reflection on its organization. Indeed, contemplating leaving his overpriced studio on Varick Street, Sorkin had been rethinking the categorization of the 2359 volumes shelved there. He never finished the task. In March 2020, the formidable architect, critic, and educator became one of the early victims of the coronavirus in New York. In the darkest days of the pandemic, his colleagues and collaborators took up the somber task of closing down the office and preserving the books in a new and permanent resting place uptown. A small group of faculty from the Spitzer School of Architecture, City College of New York approached Sorkin’s wife, theorist Joan Copjec, about bringing his library to the school where he was distinguished professor and led the urban design program since 2000. Over a few frantic weeks in April and May, they documented the office shelf by shelf, then dismantled those shelves, packed the books in some 120 boxes, and drove them in a rented van to the shut-down university building.

Piet Oudolf, Hauser & Wirth

L.M. Sacasas, the database has displaced the narrative:

Narrative is our primordial tool for sense-making, but in digital information environments narratives are framed by a more immediate experience of the Database. I’m using the term Database loosely to capture how, especially when an event is unfolding, we confront a cacophony of data points (videos, statements, claims, images, etc.) before we encounter anything like a compelling narrative of the event from a source with broad cultural authority. It’s not that we are literally presented with a relational database, but that we are confronted with what amounts to a loosely arranged set of data points, whose significance and meaning has not been baked into the form itself (as is the case with information encased in narrative). One effect of our digital media environment, then, is to immerse us in searchable databases of information rather than present us with comprehensive, integrated, and broadly compelling narratives.