Reconsidering Cranbrook's legacy and writing opening paragraphs

Last week, in the midst of a move from Brooklyn, NY to Raleigh, NC, Eye on Design published a recent essay of mine on the outsized influence of Cranbrook’s 2D Design program. It’s called How Cranbrook’s Design Program Redefined How We Make and Talk About Graphic Design and you can read it here.

It picks up a lot of threads I’ve been working through lately, notably design’s obsession with minimalism and modernism but it also continues a sort of uber-project I’ve been working on with my Eye on Design pieces that I’m referring to “as an intellectual history of graphic design”. I see this piece, in many ways, as of a kind with my recent essay on Dot Dot Dot. Both pieces take something from design history and tries to put it in a context, charting the influence beyond its time.

Like Dot Dot Dot, I think Cranbrook is often misunderstood in the design world. Design influence is usually weighted towards the coasts so the impact of Cranbrook is often overlooked. Yet, as I attempt to argue in the piece, this very small graduate program nearly singlehandedly redefined how we make and talk about graphic design. This is due, in a large part to Cranbrook’s structure and philosophy but also to the work of Kathy McCoy, the designer-in-residence and department head in graphic design from the 70s through the 90s. In writing about Cranbrook, I’ve come to think of Kathy as perhaps the single most important designer of the last generation — her influence stretches through all corners of the design world. Elliott Earls, the current designer-in-residence has continued this work and made the program a singular experience, unlike anything else in graphic design.

I hope you read it. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

I want to mention the opening paragraph briefly:

There’s a quote, perhaps apocryphal, from Massimo Vignelli that you’ll sometimes hear from alumni of Cranbrook Academy of Art’s design department. “Cranbrook”, he supposedly said, sometime in the ’80s or ’90s, “is the most dangerous design school in America.” They recite this like a badge of honor, though no one I spoke with is quite sure when or where he said it. It might have been in an interview or on stage at a design conference. Maybe it was just in conversation with a friend. But does it matter? Even if he never said it, the sentiment was (is?) shared by flocks in the design profession. The myth and mystique around Cranbrook is prone to strong emotions and bold statements. You either love it or you hate it. In 1984, for example, Paul Goldberger, the then-architecture critic of The New York Times wrote that “Cranbrook, more than any other institution, has the right to think of itself as synonymous with contemporary American Design.” And an article in Eye noted how the design department had been accused of “hermeticism, formalism, theoretical obfuscation and other crimes against the values of both classic Modernism.” I want to add my own hyperbole to the list: For the last 50 years, the students at Cranbrook have continually produced some of the most interesting, unusual, and theoretically rigorous graphic design anywhere in the world.

I spend a lot of time thinking about my opening grafs. I like to use these to experiment with structure and play with voice. Sometimes I open with a historical parallel, a joke, a quotation. Should the piece open wide or be very specific? What’s the tone, here? How do I immediately bring someone into the story I want to tell?

I was working with a lot of material for this piece and rewrote that opening paragraph more times than I can count: an early draft just jumped right into the history. Another began with the McCoy’s arrival at Cranbrook. One opened describing the campus landscape. None of them seemed quite right, either too experimental or too much like something I’d done before.

In the middle of working on this, I read Sam Anderson’s excellent profile of Kevin Durant in The New York Times Magazine. Sam’s voice is one I’ve always admired and he’s a writer I return to often. Here’s how he opened his profile:

Ok, why not, let’s start with the asteroid. Thirty-five million years ago, a giant space rock, two miles wide, came screaming out of the sky and crashed into Earth. It struck the eastern edge of the landmass we know today as North America. And it unleashed an apocalypse. The asteroid hit with the power of many nuclear bombs. It hit so hard that it vaporized itself and cracked the bedrock seven miles down. It incinerated whole forests, killed all life in the area, sent super-tsunamis ripping out across the Atlantic. You can still find remnants of the trauma (shocked quartz, fused glass) as far away as Texas and the Caribbean.

What an opening! It’s disorienting. It’s fun. It’s mysterious. I wanted something like that. My tone was too formal, too stiff. The pacing too historical. My opening paragraph is still nowhere near the levels of Anderson’s but he got me thinking about new ways to present a story. Cranbrook conjures strong reactions and firm opinions — maybe I could open with those? Instead of hiding my bias — my strong feelings for the school — I’d lead with that. I’m happy with how it turned out and felt it did what I wanted to do. Next time, I’m going to try starting with asteroids.

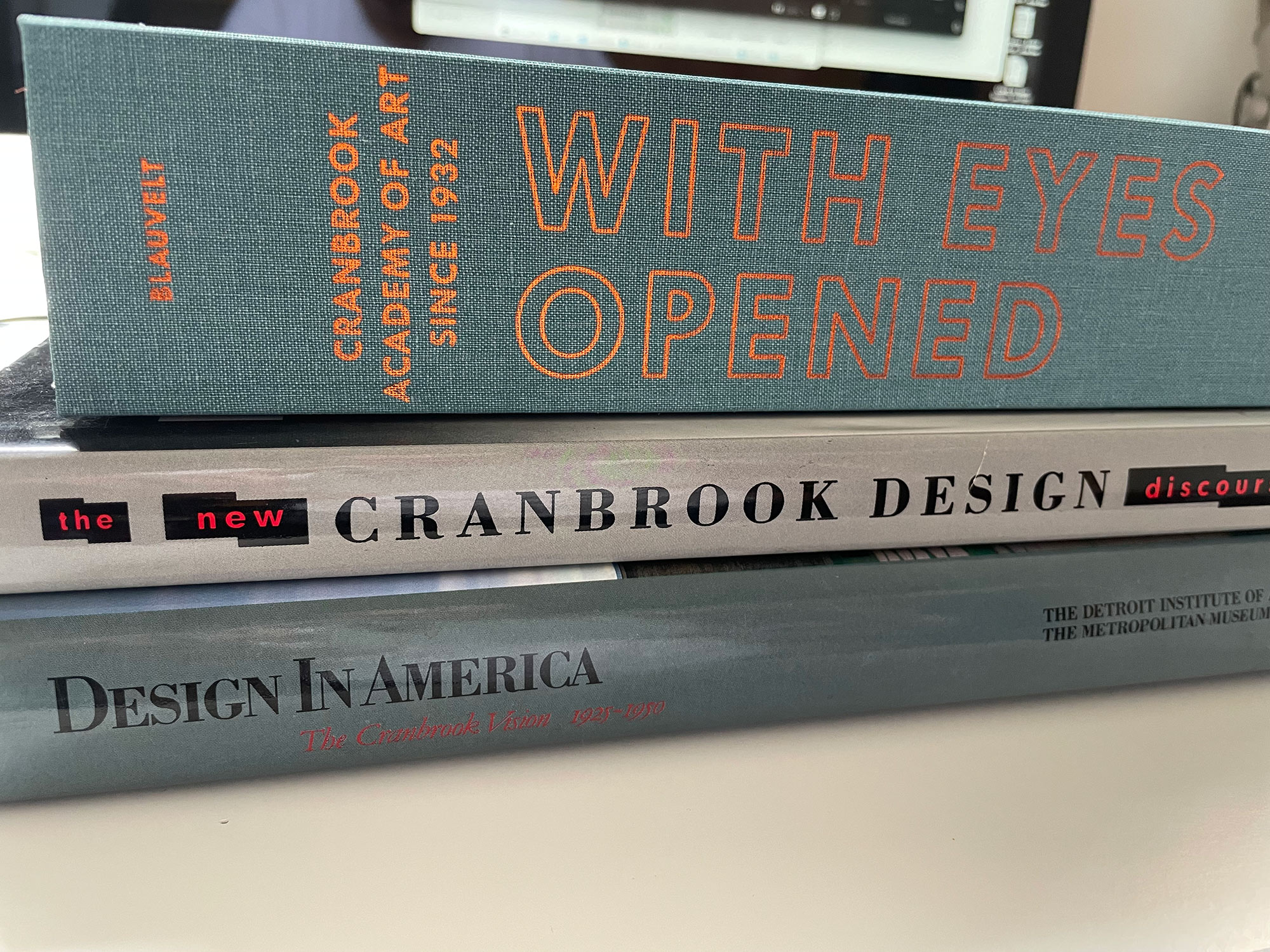

If you are interested in hearing more about Cranbrook, here’s my 2017 interview with Elliott Earls and I highly recommend looking at Andrew Blauvelt’s new show, With Eyes Opened. And, of course, you can read my essay right here. I hope you like it.