New Essay: Dot Dot Dot Is The Most Influential Design Magazine You’ve Never Heard Of

My latest essay for Eye on Design is up today — it’s on the great design journal Dot Dot Dot and you can read it here. The crux of the piece is this:

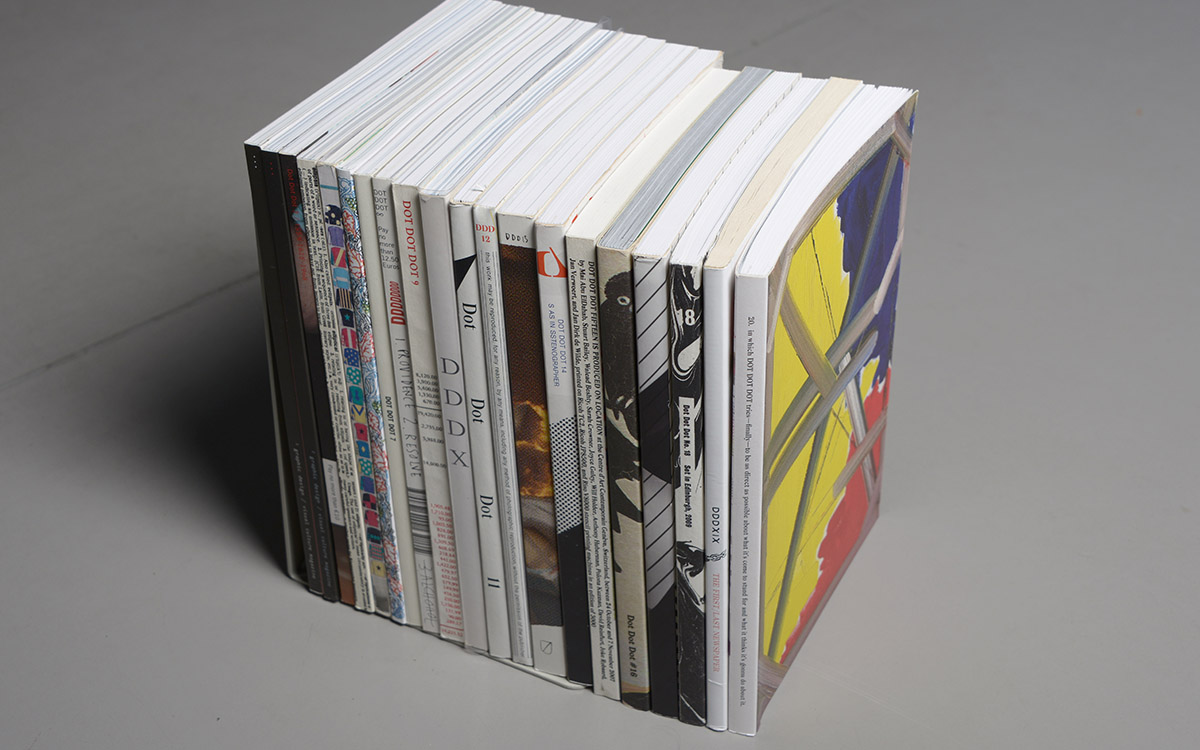

In 2005, Poynor described Dot Dot Dot as “the most stimulating and original visual culture magazine produced by designers since Emigre’s heyday in the late 1980s to the mid-1990s.” Certainly, if you were a particular type of designer in the early 2000s, Dot Dot Dot was the most exciting publication you could find. Yet unlike Emigre, the popular design magazine published by Rudy Vanderlans and Zuzana Licko through the ’90s, Dot Dot Dot was much harder to define. To try to describe it is to describe a series of contradictions: it was both high brow and humorous, exclusive and accessible, over-designed and under-designed, self-serious and self-deprecating, neither academic nor trade journal, and—as Bertollotti-Bailey said to me—“both invested in graphic design and dismissive of graphic design.” (A French publication once described its design with another contradiction: “carefully contrived flippancy.”) Moreover, to call Dot Dot Dot a ‘graphic design magazine’ is both reductive and inaccurate. Over the course of its life, it published unique and idiosyncratic stories, expanding the original design focus out into film, music, literature, and art. Despite only printing 3000 copies of each issue and ending its run a decade ago, the ethos that drove the magazine, both editorially and aesthetically, continues to influence vast sections of the design landscape. Dot Dot Dot is, perhaps, the most influential design publication you’ve never heard of.

This piece comes out of my larger, on-going research project around the history of design criticism. Dot Dot Dot, the magazine founded in 2000 by Peter Bil’ak and Stuart Bertollotti-Bailey, often gets overlooked in conversations about design writing and publishing and I wanted to highlight its run and how its influenced a generation of designers (and design publishers). As I note in the essay:

In retrospect, Dot Dot Dot launched at a peculiar time for media, and especially design media—caught in the transition from a print dominated media system to a digital one. It sat in between the explosion of design writing during the ’90s, when publications like Emigre and Eye offered a future of rich design criticism and the weblogs of the late 2000s like Design Observer and Speak Up, a prelude to our current social media-driven world.

Dot Dot Dot wasn’t part of the explosion of criticism in the 90s but it also was just before the rise of blogs. Add to this, by only printing 3000 copies of each issue, it was often hard to come by, cultivating a cult-like status for a specific type of designer in the early 2000s. I was one of those designers. I discovered DDD towards the end of its run — via Rob Giampietro’s Lined and Unlined, I think — and saw a way of practicing design that felt new and different to me, and a type of discourse I wanted to be a part of. It wouldn’t be until years later — in 2015 — that I actually saw a printed issue!)

I note this way of practicing design is one that comes out of a paradox: both taking graphic design really seriously while also being disinterested in graphic design. This way of work can also be seen in the 2007 exhibition Forms of Inquiry and signal a shift in design from ‘designer as author’ to designer as researcher’ and what often gets bundled together under the term ‘critical design’:

As Francisco Laranjo noted in Modes of Criticism, the rise of critical design marked a shift from ’90s-era ‘designer as author’ to the more expansive ‘designer as researcher.’ This, perhaps, explains Dot Dot Dot’s move from a magazine about graphic design to one from graphic design — graphic design becomes a lens through which to understand and interrogate adjacent aspects of culture. Laranjo cites Werkplaats Typographie, the Dutch graduate program founded by Karel Martens where Bertolloti-Bailey was a student, and Yale’s MFA program, where Reinfurt was a student, as sources for a way of thinking that use design as a starting point to generate new discourses. A subtext that can be read in the writing of many of these designers is a frustration—and perhaps disaffection—with graphic design as it is traditionally practiced. The key, however, is that this frustration results not in an abandonment of the profession but rather is channeled towards a belief that graphic design can exist outside a traditional client-designer model, becoming a mode of cultural production.

But what really interested me was how you can see the Dot Dot Dot DNA across the design field — all sorts of publishers, critics, writers, and book publishers have seemed to have continued the ethos of using graphic design as a lens through which to examine culture. For the piece, I talked to Peter and Stuart, as well as David Reinfurt who took over as co-editor in 2005. I also talked with contributor Rob Giampietro and Matthew Stuart and Andrew Lister, the editors of Bricks from the Kiln, a new journal that very much feels like a new version of DDD.

In many ways — as with so much of what I write about — I went in thinking I knew the story only to discover it would be about something else. What struck me in the reporting and writing of this one was how much my own work is also part of this lineage. On the one hand, Scratching the Surface — and much of the writing I do — comes from a place of trying to build a bridge between professional and academic writing on graphic design. When I spoke with Peter Bil’ak, he articulated this as a goal from the outset of DDD.

But the bigger theme that came out of this was DDD’s editors disaffection with graphic design. Bertolotti-Bailey described DDD as both taking design seriously and being dismissive of design. This paradox — of both thinking about design rigorously and dismissively — can be seen in how the editors talk about the journal, the writing itself, and in the move away from strictly design topics. This, perhaps, is the biggest influence of DDD. There is a wide range of practitioners who can’t describe the feeling of both loving design — of dedicating their lives to it — while also feeling disaffected by the whole enterprise. I include myself in that, by the way. That feeling can lead to two paths: you either walk away and find something new to do. Or you double down, you go to grad school, you write polemics, you start a podcast, anything to find your way back into it and remind yourself why you liked it in the first place. For those who frequently get disenchanted with graphic design — and god knows I’ve felt that — Dot Dot Dot showed us an alternative. It showed us how to turn it into something else.

Thanks to Peter, David, and Stuart for talking to me for this. As well as Rob Giampietro for his helpful conversation and Andrew and Matthew of Bricks from the Kiln for their generous perspective in the research.

You can read the entire piece over on Eye on Design.