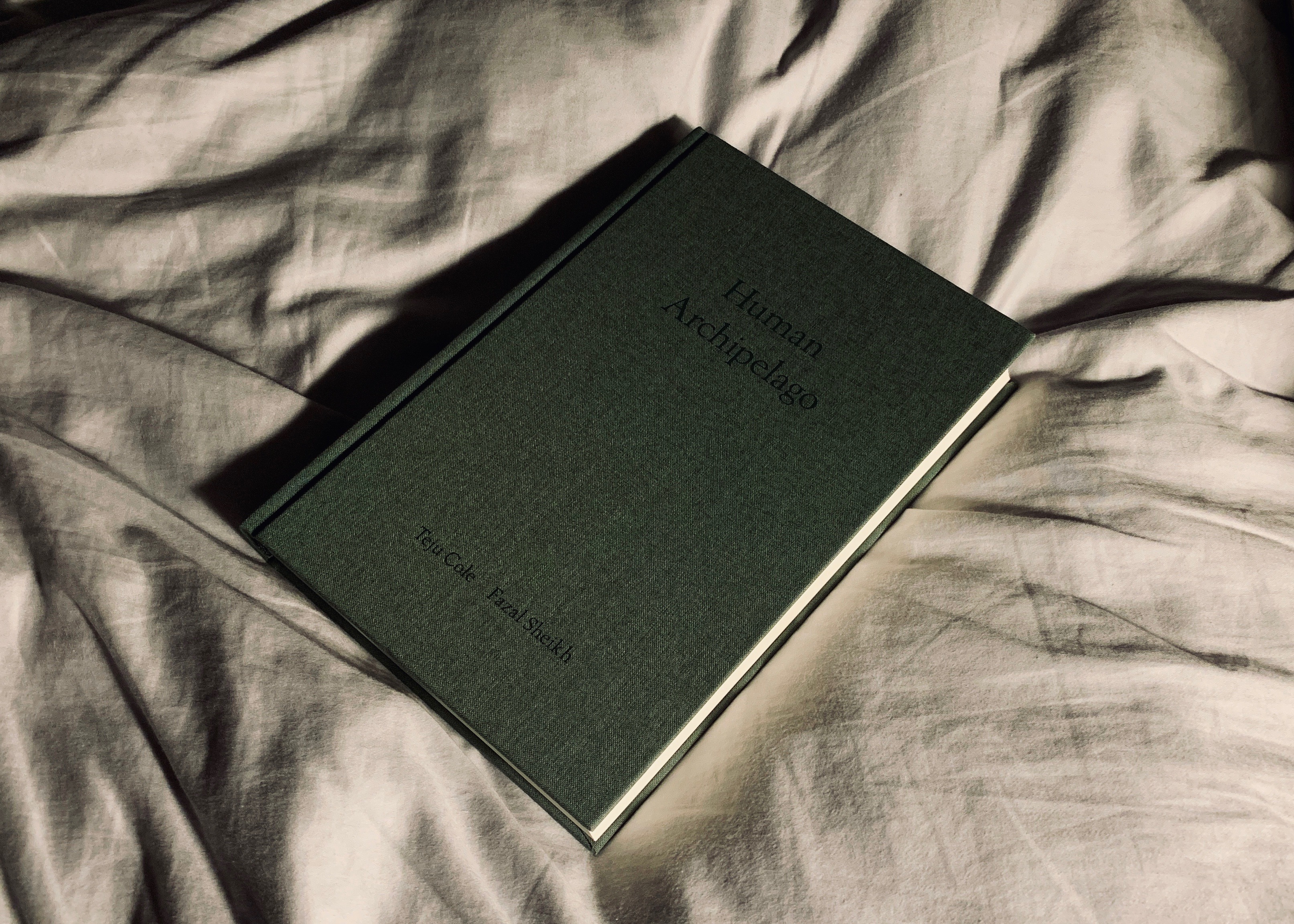

Human Archipelago

The striking black and white portraits are mixed with austere landscapes and abstract aerial imagery. Between the photographs we find fragments of text — sometimes its poetry and epistles, other times quotations and questions. The opening page asks us:

Who is the stranger?

Who is kin?

What do we owe each other?

What, in the inferno, is not infernal?

The book is Human Archipelago, a new collaboration between photographer Fazal Sheik and writer Teju Cole, and it’s these questions that we are forced to confront as we move through the book. Published in a beautiful package by the German publisher Stiedl, Sheik’s photographs of the displaced and the dispossessed around the world and Cole’s texts alternate page to page, raise questions about immigration, about refugees, about migration, hospitality, humanity.

These are themes the two return to often in their work. Their work has always had a political dimension — the photography column Cole wrote for the New York Times had a political dimension from the first essay — but when they come together, there’s a new clarity in these themes. Created in response to the current political climate — when questions about immigration, nationalism, and refugees are on so many minds — the collaboration goes deeper, stretches further, and rises above the political fray, making a quiet call for our common humanity. “Modern hospitality, on the other hand, must countenance both human duty and human rights,” reads the middle of the book, “Care of the other must reckon with the other as human here in our domain as well as over there in hers.” We read these words while staring into the eyes of a subject from one of Fazal’s portraits. The gaze goes both ways. We are looking at them but they are also looking at us. We must see each other, acknowledge each other.

Cole’s writing draws on the style he has been experimenting with on Instagram for the last few years and was collected in his 2017 book of photos and text Blind Spot. Writing elliptically through fragments, quotations, epistles, poetry, journal entries — a lyric poem of sorts — Cole at times references the photo and at others diverts our attention from paired image. In Blind Spot, Cole’s text and photographs were somewhat reflexive — about the act of looking itself — here, these fragments add up to a clearer thesis, the fragments subtly building to an end goal. The fragmented sequencing — no entry is more than a page, some merely a few lines — can obscure a directness that was largely absence in Blind Spot. Here’s Cole in one of the opening pages:

We are always looking forward and backwards, inside and out. We are not what we see. Doubleness is the first condition of the human. We are not ourselves without also being the Other.

The language, never losing its poetry — or all of Cole’s favorites: Berger, Tranströmer, Homer, Morrison — is somehow more forceful, more pointed. “Why do you, as a black person in America, feel you are allowed to be here?” Cole asks, “Can you prove you are human?”

For so many of us who make things, we’ve sometimes struggled with how to respond to the horrific national news over the last few years. What is the role of art, of design, of poetry, of writing? Are we leaders of the resistance? Do we fight back? Sheik and Cole provide an example of another way forward. The path of refusal. “The meditative aspect of the book is also important. When we’re facing such astonishing things, as we are right now, a lot of the response can be noisy,” Cole said in an interview about the book with City Lab, “We are shell-shocked right now, and yet our most deeply human self wants to be contemplative and sit with something quieter.”

The sequencing gives Sheik’s images a cinematic quality, shifting from the micro and the macro, zooming in to the individual before pulling us back to the terrain. This is a metaphor of migration. As we turn the pages, we, too, are moving. “There are no refugees,” reads the book’s final page, “only fellow citizens whose rights we have failed to acknowledge.” This shouldn’t feel subversive, but in the world we now find ourselves, it somehow is.