Wormwood and the Collage Method

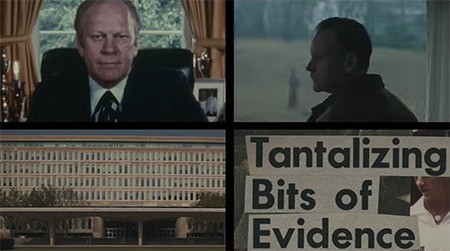

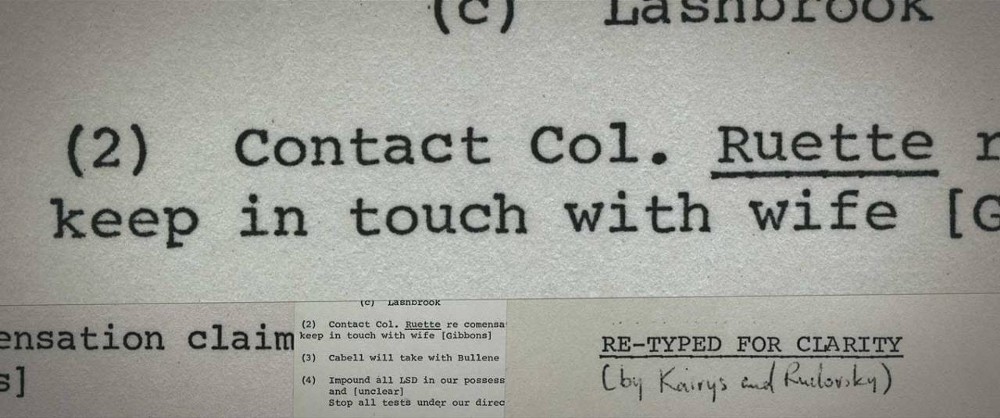

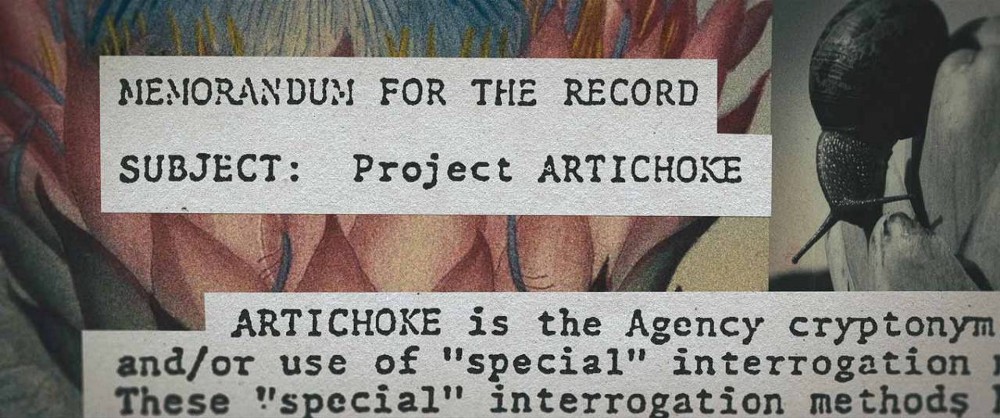

Wormwood, the new Netflix series from Errol Morris, tells the story of the mysterious death of scientist Frank Olsen. Olsen plunged to his death after falling or jumping out of a hotel window in New York City in 1953, seemingly a suicide. We quickly find out, however, that Olsen was part of an experiment conducted by the CIA, known as MK-ULTRA, that gave scientists LSD without their knowledge to identify procedures to control behavior and retrieve admissions in interrogations. But as with any Morris film, this is just the beginning. Morris’s story centers around Frank’s son, Eric, who’s spent his life trying to uncover the circumstances around his father’s death, going as far as to exhume his body nearly forty years later. Part documentary and part scripted drama, Morris moves between a traditional documentary format and a highly-stylized suspense story making the six-part special possibly the best thing he’s done.

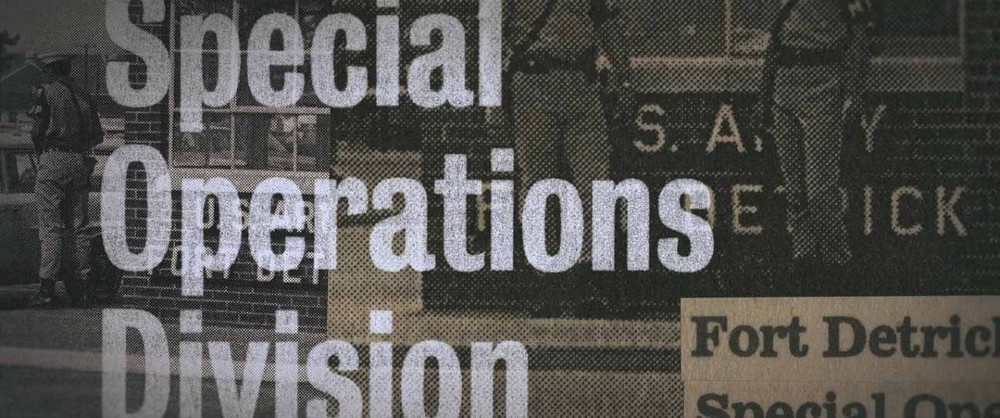

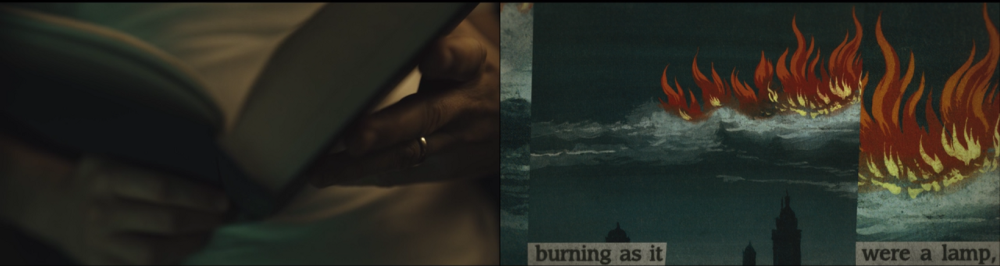

I was immediately taken with the editing — mixing documentary, drama, found and archival footage, interesting cinematic techniques like split screens and various film ratios — I remarked after the first episode that it almost felt like a video essay. What tied these diverse styles together, however, were recurring interstitial graphics where Morris and his team collaged headlines from newspapers, archival photographs, textures, and film stills to introduce key events, characters, and plot-lines; often reminding me of the stereotypical shot of the investigator standing in front of a bulletin board filled with newspaper clippings and photographs, red string visualizing the connections in search of the truth.

We learn in the second episode that Eric studied psychology at Harvard and centered his work on something he called the “collage method”. Morris doesn’t spend much time on this — Olson talks a bit about his process and we’re shown a few collages he’s made — before returning to the central story. Collage has been a central research project in my own work and fundamental in my own creative process so I was, obviously, immediately intrigued. In doing some research upon finishing the series, I discovered Olson’s personal website where he’s written extensively about collage and the collage method, introducing it in his essay called Chaos, Creation, Collage:

The Collage Method consists of a progressive sequence of physical activities and a closely correlated series of therapeutic interviews. Taken one by one the physical activities of collage-making appear disarmingly simple, so simple in fact that their significance easily escapes notice. However, when they are taken together, as an integrated series of transformations, a quite surprising symbolism appears. The activities entailed in making and physically transforming collages can then be seen to embody the logic of psychological development. These activities comprise an extended metaphor: they symbolize the growth of the human mind.

This correspondence between a series of ‘simple’ activities on the one hand, and a subtle developmental logic on the other, is the key to the Collage Method. Thanks to this correspondence, the Collage Method enables the collage maker to re-trace, in a forward direction, the path by which the psyche develops in infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

Morris — subtly and explicitly — uses this as a formal framework through which to tell Olson’s entire story. All the graphics in the series, designed by graphic designer and frequent Morris collaborator Jeremy Landman, use this as the starting point. But more than than that, the entire series becomes a type of montage — the cinematic equivalent to collage — jumping between format, time, and style to create a coherent whole.

In an essay I wrote last year about collage and the creative process, I said:

Collage is synecdochic of the creative process. It’s our process made visual. The design process always begins with collage. We may have moved from the traditional cut-out and pinned-up moodboards to digital Pinterest boards — but the action is the same: we pull from our influences and inspirations, using the fragments of what came before in search of something new. Design is both a noun and a verb, the action and the artifact and so is collage. It is a noun — a complete object — but also a verb — the action of collaging, of connecting disparate parts into a coherent whole. In my first design classes we learned about gestalt, that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”. Collage reflexively teaches gestalt — a single work that also reveals the individual elements. All design is, in essence, collaged. It’s is taking preexisting forms — shapes, typography, images — and collaging them into a coherent whole. And the same is true for the writer — where the designer pieces together shapes and imagery, the writer pieces together words. A sentence a collage of words; a paragraph a collage of sentences.

The same is true of documentaries; of storytelling. And in many ways, this aesthetic feels perfect for Morris who has long been fond throwing bold newspaper headlines up across the screen while interjecting his stories with found footage. When Vulture’s Matt Zoller Seitz’s asked Morris about the collages, he answered:

Here’s my line, for what it’s worth: The best nonfiction asks us to examine the relationship between what we’re seeing on the screen and the real world. It makes us think about that. It doesn’t lull us into some kind of acquiescence or blind acceptance. It makes us think about how stories are constructed, how they’re put together. Napoleon had this really cynical line, which I disagree with. The line was, “What is history but a collection of agreed-upon lies?” What’s interesting is that so much of history is an agreed-upon lie, but still, history stands outside of us, in that sense that something happened in the real world, and just mere agreement between men and women will not make it so.

This, perhaps, is the story of Wormwood. Perhaps the truth cannot be known — people with answers are dead. Perhaps the story is actually about Eric, the son, and his lifelong quest for answers, constantly reliving these memories, collaging them together in new ways. I’m reminded of the quote I used to close my collage essay last year, from the architect Juhani Pallasmaa: “Our very consciousness is an ever-changing collage of mental fragments held together by one’s sense of self.”